“Rescue the weak and needy; deliver them out of the hand of the wicked…” Psalm 82:4.

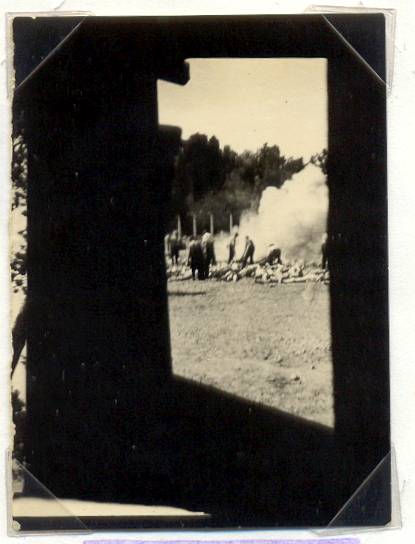

Note: this is part three in a series of essays examining the issue of abortion biblically. Click here for part one, and here for part two. Content warning: this essay contains a graphic photo that may be unsettling for some.

The Cost of the Concubine

It has been three days of carnage. Your brothers, relatives, and friends, along with sixty-five thousand other men, lay strewn about the countryside, their bodies split open, pierced through with arrows, their heads crushed by sling stones or decapitated from their necks. You weep for their deaths and you weep because you have just won a war you never wanted to fight, one waged not against your enemies but your own countrymen. Though your eyes are clouded by tears, in your heart there is clarity—the war was right. It could have been avoided, but its avoidance would have been a grievous sin.

Such was the state of mind of countless Hebrew men during an episode in the book of Judges. In its twentieth chapter, civil war breaks out between the tribe of Benjamin and the other tribes of Israel. It is a bloody conflict that culminates in the near extinguishment of the Benjamite tribe from among the sons of Israel. What led to such an extreme and costly tragedy? As it turns out, it was little more than the refusal of the people to bring a single crime to justice.

In Judges 19, a Levite traveling with his concubine through Israel comes to the town of Gibeah in the territory of Benjamin; he accepts the offer of an elderly gentleman to have him and his concubine sojourn within his dwelling for the night. All appears to be well and merry as the Levite and his concubine sup and enjoy the hospitality of their host, yet unbeknownst to them, worthless men with cold hearts and burning lust have slunk out from their homes and surrounded the house. Pounding on the door, they make their presence known, along with their demand: they want the Levite brought outside so they can gang-rape him.

There’s a bit of argumentation between the old man and the band of degenerates, but everything is settled when the Levite seizes his concubine and selfishly throws her out like a bone to a pack of stray and rabid dogs. Until the break of dawn she is raped over and over again with such violence that when they are finally finished with her, she staggers back to the house, collapses in its doorway, and breathes her last. When the morning comes, the Levite, finding her dead, takes her back home. We are told:

29 When he entered his house, he took a knife and laid hold of his concubine and cut her in twelve pieces, limb by limb, and sent her throughout the territory of Israel. 30 All who saw it said, “Nothing like this has ever happened or been seen from the day when the sons of Israel came up from the land of Egypt to this day. Consider it, take counsel and speak up!”

(Judges 19:29-30)

What the men of Gibeah did was so ghastly and wicked that even after cutting the woman into twelve separate pieces, the tribes could examine the portion of her body sent to them and ascertain by looking at it that she had been the victim of unfathomable abuse. The crime galvanizes the entire nation to unite as one man and seek justice for the gang-raped and murdered concubine. The allied tribes send a message to the tribe of Benjamin: “What is this wickedness that has taken place among you? Now then, deliver up the men, the worthless fellows in Gibeah, that we may put them to death and remove this wickedness from Israel” (Judges 20:12-13).

The request was a reasonable one that the tribe of Benjamin themselves should have been eager to carry out. What kind of people would not want to see swift justice dealt out to those worthless men, let alone tolerate people of that sort dwelling among them? Inexplicably, however, the tribe of Benjamin refuses; they decide to protect the men of Gibeah and gloss over their misdeeds, taking up arms to fight against the rest of the nation in the process. With civil war looming, why didn’t the rest of Israel just back down? Why not just leave the Benjamites alone? What the men of Gibeah did was beyond horrendous, but was avenging the mistreatment and murder of one life worth the spilled blood of thousands of others?

The fact of the matter is, the request made by the tribes was not only a reasonable request, it was a necessary one. They needed to put those men of Gibeah to death. It was the only way to, as they said, “remove this wickedness from Israel.” As we saw last time, God requires justice for the shedding of innocent blood. Bloodshed brings bloodguilt, and bloodguilt can only be atoned for by bloodshed. When a people fail to render justice for bloodshed, they too become marked with bloodguilt. In this manner, a nation becomes quickly polluted with blood and their land defiled with wicked abominations. Injustice and inaction mix together to form a deadly brew that poisons entire societies. God had made it clear in the Torah that when a nation becomes defiled, ruinous calamities from his own hand are not far behind. So the rest of the tribes really didn’t have a choice in the matter. Even if they were not driven by holy outrage and a zeal to carry out the LORD’s ordinances, they would have been disobeying at their own peril. The price for failing to pursue justice is very high indeed. Yet, as Judges 19-21 shows us, that does not mean the price for pursuing justice will be cheap. It can, as we shall see, be quite costly.

Clean Hands, Clear Eyes

As followers of Christ, we must know what to do when faced with the shedding of innocent blood. For his namesake, and for the sake of our souls that will one day stand before his throne for judgment (1 Peter 1:17), we must know exactly what is required of us. This is true of all forms of bloodshed, but especially so of abortion, since it is without contest the greatest source of blood-pollution in our nation and many other nations of the world today. If God destroys entire societies over the shedding of innocent blood, then we are in urgent need of having a divinely-prescribed response.

The twenty-first chapter of Deuteronomy provides a good starting place to understand what is required of us. It says:

“If a slain person is found lying in the open country in the land which the Lord your God gives you to possess, and it is not known who has struck him, 2 then your elders and your judges shall go out and measure the distance to the cities which are around the slain one. 3 It shall be that the city which is nearest to the slain man, that is, the elders of that city, shall take a heifer of the herd, which has not been worked and which has not pulled in a yoke; 4 and the elders of that city shall bring the heifer down to a valley with running water, which has not been plowed or sown, and shall break the heifer’s neck there in the valley. 5 Then the priests, the sons of Levi, shall come near, for the Lord your God has chosen them to serve Him and to bless in the name of the Lord; and every dispute and every assault shall be settled by them. 6 All the elders of that city which is nearest to the slain man shall wash their hands over the heifer whose neck was broken in the valley; 7 and they shall answer and say, ‘Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it. 8 Forgive Your people Israel whom You have redeemed, O Lord, and do not place the guilt of innocent blood in the midst of Your people Israel.’ And the bloodguiltiness shall be forgiven them. 9 So you shall remove the guilt of innocent blood from your midst, when you do what is right in the eyes of the Lord.

(Deuteronomy 21:1-9)*

Here the Lord details how the Israelites are to free themselves from the bloodguilt of an unsolvable crime. They know that there has been a transgressor in their midst but they have no way of bringing him or her to justice. Hence, the usual form of atonement, which involves shedding the perpetrator’s blood, cannot be done. In this case, a heifer is killed—perhaps as a substitute for the life of the unknown assailant—and the elders and Levites intercede on behalf of the nation, asking for mercy and forgiveness over the blood that has been shed.

This passage provides many principles on how a people are to handle bloodguilt, but for our purposes, we shall draw our attention to the statement made by the elders in verse seven. To have their land freed from the guilt of shed blood, the elders, who stand as representatives for the entire community, had to be able to truthfully confess two things: one, that they did not shed the blood; and two, that they did not see it. Not only did they have to claim abstention from the act; they had to profess a lack of knowledge as to its going on. They could be neither actors nor witnesses to the deed. Then and only then would the bloodguiltiness be forgiven them.1

It is easy to see why this is the case. If they were witnesses to the shedding of innocent blood and did not try to stop it, or being unable to stop it, did nothing afterward to bring the transgressor to justice, they would be complicit in the bloodshed. What their eyes saw demanded a response from them. In this case, their failure to participate in the act does not absolve them, because their failure to intervene in the act condemns them. Clean hands do not absolve you of slack hands when your eyes witness evil. Remember the reaction of the tribes of Israel when they saw the dead concubine’s body? The witness requires a response. For those who witnessed but did not participate, their hands were soiled with blood not by what they did, but by what they refrained from doing.

This joint innocence of hands and eyes hearkens back to the principles of bloodshed elucidated within the previous essay in this series, which detailed how the sin of bloodshed can be committed through active and intentional participation or acts of negligence. In one case, it is an action that brings bloodguilt; in the other it is inaction. Bloodguilt comes both from committing murder and from failing to bring the act of murder to justice. But as we see here and as we shall see from other scriptures as well, it also comes from failing to intervene. This is because the pursuit of justice is not simply something done after an evil is committed; it also involves what individuals do while an injustice is being committed.

Christian Bloodguilt

The straightforward implication of Deuteronomy 21:7 is that if you knew that the shedding of innocent blood was going on and you did nothing about it, you have bloodguilt. If it has not dawned on the reader yet, let it be made explicit: many people who believe abortion is wrong, and who recoil at the thought of ever doing it, have the bloodguilt of abortion on their hands. This tragically includes many people within the Church. Few, if any of us in the Church can say, “Our eyes did not see it,” even if hopefully most of us can say, “Our hands did not shed this blood.” Too many of us have mistaken moral disgust at the shedding of innocent blood and a personal commitment not to engage in it as absolution in the matter. But unlike the elders, we cannot wash our hands over the slain heifer; we are not unaware of what is going on.

We know there are centers all over this nation where people are lawfully murdering their children every day. We know that justice is not being sought for those murders. We know that right now, there are politicians in our state and nation’s capital using their power to ensure that the slaughter of unborn children remains unabated and unhindered and even broadened in scope. We know that there are corporations and various organizations pouring in millions of dollars every year to ensure this legal, systemic apparatus of murder is well-funded and successful. The question is, what are we doing with all this knowledge? Sadly, the answer for too many of us is—not much.

Do we feel the weight of this? Or even now, are we so lethargic in heart that we cannot be stirred to conviction? Dearest Christ-follower, mark deep within your soul: bloodguilt is not just on those who shed blood, but on those who do nothing to halt it and who do not labor for the fruition of justice.

The first order of business for the people of God, then—in seeking to respond rightly to the shedding of innocent blood—is to deal with our own bloodguilt. We must repent for the ways our hands are stained. For some it is the confession of both having had an abortion (directly as the mother, or indirectly as the father of the child, or as someone who encouraged or pressured a woman to do so) and of not seeking justice for the unborn; for others, it will simply be a repentance of their inaction and complacency.

But let not those guilty of only the latter and not the former be preoccupied with whatever great measure of guilt they suppose those who have had an abortion carry. A man about to stand trial for murdering one person does not reason that he shall be acquitted due to another having killed two, and he would be foolish to plead for mercy by pointing out the greater severity of the other man’s crime. One does not escape dreadful consequences by comparing another man’s bloodguilt with his own. So it is with us. In the fear of God and with genuine anguish over own bloodguilt, we must rend our hearts and not our garments, and confess to God that our eyes have seen and we are guilty of inaction. We must not look firstly to others and what they have or have not done; the first task is to look at ourselves until our heart breaks.

An Inescapable Commission

Our repentance in this matter is not simply to absolve ourselves of all the abortions that have already happened in our nation; it is just as much to ready us to adopt a posture of action that will prevent more bloodguilt from being heaped on our heads. As John the prophet enjoins us, true repentance bears fruit (Luke 3:8). It is not just grief over past behavior; it is a change in behavior for the present moment and the future. And in our present moment, unborn children are being slaughtered every day.

In this regard, Proverbs 24:11-12 are key verses that show us what the response of God’s people to the horror of abortion is supposed to be—and what God will do to those who do not respond.

11 Deliver those who are being taken away to death,

And those who are staggering to slaughter, Oh hold them back.

12 If you say, “See, we did not know this,”

Does He not consider it who weighs the hearts?

And does He not know it who keeps your soul?

And will He not render to man according to his work?

(Proverbs 24:11-12)

We know that everyday unborn children are being taken away to death. And God makes clear in that situation that it is not enough to just say we did not personally participate in the killing. What God requires of us when we see people staggering to slaughter is to hold them back. To intervene. To get right in the middle of their march towards the cliff’s edge, dig in our feet, and with arms spread out, halt the advance. To stand between the victim and the killer and their instruments of death and say, “Not on my watch!”

When we see a Planned Parenthood clinic on a street block in our city; when we see councilmen or senators or mayors seeking to keep the murder of the unborn legal; when see pastors blaspheming the name of Christ by saying God is pro-choice; God has a word for us: “Deliver those who are being taken away to death.” There are certain commissions for the people of God that are automatic. When we see a group of people being taken away to the slaughter, in that very moment, God commissions us to be a deliverer. When the lives of innocent people are at stake you don’t get to decide whether you opt in or not—you’re in. Taking action on a situation like abortion, then, is not a nice and noble option; it is a sacred duty, bound up with our identity as one whom by the blood of the lamb is righteous. Inaction is off the table. Because we have seen, we must act. To do otherwise is to be under the bloodguilt that pollutes nations and brings God’s horrible and mighty wrath.

Blind & Far Away

Of course, it would be very convenient for us if we could say that our eyes have not seen the evils of abortion. If knowledge necessitates action, then ignorance would seem perhaps to validate inaction, and many people not wanting the burden placed upon them of having to do something will be tempted to claim ignorance in these matters. This is precisely what verse twelve is getting at. God recognizes that there will be people who will want to claim, “See, we did not know this.” But to uttering words like this we are warned: “Does He not consider it who weighs the hearts? And does He not know it who keeps your soul? And will He not render to man according to his work?” In effect, God is saying, “Don’t pull that on me, I won’t fall for it!” He will see right through our protestations of ignorance and he will judge us for doing nothing. If we say, “our eyes didn’t see it,” he will say, “No—your eyes did.”

The pattern of thought outlined in verse twelve is unfortunately common to history and human nature. In the face of every ongoing atrocity, there has been a temptation for people to blind themselves to the horror of what is really going on so that they are not faced with the responsibility of doing something about it. This has proven to be true with slavery and with the lynchings and other Jim Crow injustices of the South, as well as the Holocaust and other genocides throughout the 20th century. People within the nations those atrocities were committed too often looked away or feigned ignorance. Why?

The sad and simple reason people do not want to do anything about the shedding of innocent blood is that humans have a tendency towards selfishness, and an impactful response to the shedding of innocent blood will often not just be inconvenient, it will often time be costly— sometimes to a tragic and stupendously large degree. Such was the case of the concubine: a righteous, God-honoring response cost the nation a civil war. While the cost of pursuing justice may rarely reach such agonizing heights, standing up to an evil that has firmly entrenched itself within society is never a walk in the park. It breeds fierce opposition, it is laborious and above all else, it requires self-sacrifice—not just of time, but of resources and often one’s reputation as well; at times it endangers oneself and one’s family, and may ultimately result in the high price of their life and your own. No wonder many try to pretend they don’t see what is going on. The glory and nobility embedded within the word “justice” are not tasted of easily, for all that we romanticize its pursuit and for all the casual veneration we bestow upon it; it is not a cheaply worn glamour; its glory is a Christ-shaped one—one wrought by suffering. And if there is one thing humans are tempted to loathe more than the suffering of others, it is their own.

As it pertains to abortion, this willful blindness does not take the shape of outright denial of its existence—as if one had lived under a rock their whole life and had never heard what abortion was. Rather, it is accomplished by means of moral obfuscation; of stripping abortion of its moral horror and turning it into something ambiguous and complex so that a response against it is no longer required—or by simply appealing to the sheer normality of it. It is hard for the human heart to remain horrified by what is commonplace, especially when there is ample sand for which to bury our heads in and we are able to go about our day to day lives without having to think about it or see it.

This obfuscation is found in the litany of everyday expressions and rebuttals surrounding the issue of abortion: “You know, it’s not that black and white; whose going to support the mother? What if she cannot afford it?” Or, “What about the lack of availability of contraceptives? What about maternity leave?” Or, “No woman comes to this decision easily,”—as if the economic hardship or the intensity of the deliberative process somehow renders the moral status of killing another innocent human being uncertain. By drowning the issue of abortion in a sea of nuances, we attempt to stop the heart of its diabolism that beats loud and clear so we don’t have to listen to it. We turn simple arithmetic—a concise syllogism of moral logic2—into a calculus problem, long and difficult to solve3. We twist it into something our consciences can feel justified to ignore.

We see this desire to ignore injustice and therefore avoid responsibility to take action in the parable of the Good Samaritan. If you remember in Luke 10, Jesus tells the story of a man robbed and severely beaten while traveling to Jericho. He is left wounded and bleeding and “half dead” on the road. When a priest later travels down the road, he sees this man who has just suffered a horrible crime and decides to pass by him by crossing over to the other side. A Levite later comes and does the same. What were they doing? They were trying to create as much distance from the man and themselves as they could so as to avoid the responsibility of helping him and the guilt of not doing anything about it. If you recall from Deuteronomy 21, it was the city nearest to the slain victim whose elders had to sacrifice the heifer. Here, both the priest and Levite go out of their way (literally) to artificially create less proximity to an injustice. They did want not the burden a righteous response would bring. The very people who were supposed to represent God to their nation proved themselves to have a disposition contrary to his heart that burns with compassion and justice.

When we scroll by social-media posts about abortion without stopping to ponder the horror of it all; when we try to console ourselves that there are many legitimate causes to be part of and of course, we can’t be part of them all; when we allow ourselves to be deluded by society’s arguments in defiance of the clear weight of scriptures so that abortion is transformed into a murky, morally ambiguous subject, we do the same thing as the Levite and priest. We create distance for ourselves that would not be there if we walked truthfully and allowed ourselves to see the bloody injustice on our path lying right at our feet. We claim blindness to avoid God’s commission of intervention and deliverance—and this God sees.

Love is the Price We Pay

Inaction in the face of injustice was one of the main and abiding concerns of the Old Testament prophets, and the repeated failure to come to the aid of the afflicted and mistreated was one of the main reasons God ultimately decided to judge the nations of Israel and Judah. Prayer, worship, and forms of religious ceremony however rigorously undertaken did not produce pleasure in the heart of God but rather exasperation and disgust in his people when they were done in concert with idleness towards injustice. Amos reveals the heart of the Lord when he declares by his Spirit:

21 “I hate, I reject your festivals,

Nor do I delight in your solemn assemblies.

22 “Even though you offer up to Me burnt offerings and your grain offerings,

I will not accept them;

And I will not even look at the peace offerings of your fatlings.

23 “Take away from Me the noise of your songs;

I will not even listen to the sound of your harps.

24 “But let justice roll down like waters

And righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

(Amos 5:21-24)

God’s call for his people was to pursue justice with such vigor and dedication that justice would seem to be inundating the land like a rainstorm that soaks the ground. They were to contend for righteousness to manifest in their nation with the constancy and power of a river that never stops flowing. This was not to be done in place of their gatherings of prayer, worship and instruction, but rather pursued in tandem with those other forms of devotion. All of them were to be included holistically in a life poured out to God in an act of spiritual worship. Justice was never meant to be an optional expression of a godly man or woman’s devotion, it was always meant to be part of the integrated whole of their obedience and loving service to Christ.

8He has told you, O man, what is good;

And what does the Lord require of you

But to do justice, to love kindness,

And to walk humbly with your God?

(Micah 6:8)

17 Learn to do good;

Seek justice,

Reprove the ruthless,

Defend the orphan,

Plead for the widow.

(Isaiah 1:17)

What then, as it pertains to abortion, is God looking for? The seeking and doing of justice is required of us—but what does that look like? The particulars of pursuing justice and intervening in the lives of the unborn will be chronicled in more depth at a later time— the ways both biblical and practical we can get involved—but the truth is, while there are concrete steps we can and should take, the exact expression of justice over the issue of abortion will look different for each person. What matters more than the actions themselves is the spirit and attributes that attend them.

In Luke 10, Jesus contrasts the deeds of the priest and Levite (those who shirk from their God-given duty of pursuing justice) with the actions of the Good Samaritan.

33 But a Samaritan, who was on a journey, came upon him; and when he saw him, he felt compassion, 34 and came to him and bandaged up his wounds, pouring oil and wine on them; and he put him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn and took care of him. 35 On the next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper and said, ‘Take care of him; and whatever more you spend, when I return I will repay you.’

(Luke 10:33-35)

Notice first, that the Samaritan was on a journey; he was not wandering about in his spare time looking to be a good-doer, he was involved in conducting the affairs of his life just as much as you and I; his actions were therefore inconvenient and interruptive to his daily life. Second, his actions were not done with dry or begrudging obedience to the dictates of his religion; they were deeds animated by love. Third, his actions were costly; they cost him his time and money. And here it is important that we mark the character of his cost. How much did the Samaritan pay? As much as was needed for a full recovery. The Samaritan did not tell the innkeeper, “Well, I’ve done my part, now it’s up to you to bear some of the cost and see to it that he is restored.” On the contrary, the Samaritan’s commitment was to see it through to completion.

Our response to injustice should be likewise. It must cost us something; something of ourselves must be sacrificed. It must be rooted in love and seen through to the end—for that is the type of cost love pays; love perseveres, it stays constant and implacable, it gives as much as is needed to satisfy its aim. Love never quits, and as such, it never fails. In the final estimation, the pursuit of true justice looks like the one who pursued it perfectly: Christ our Lord. Before the cross, untold billions stood as enemies of God. Mankind’s embrace of sin constituted a heinous rebellion against the Lord fully deserving of devastating recompense. How to right this cosmic injustice? It would have been wholly just if Christ had condemned the whole of humanity to everlasting torment for rebellion against his Father. Instead, he rendered justice by offering himself as a guilt offering; he was pierced for our transgressions, he let the Father crush him for our iniquities (Isaiah 53:5-6,10). His pursuit of justice was one of self-sacrifice, and what can those of us who are truly grateful for it do but humbly strive to walk in the same way?

In the end, we must realize our failure to pursue justice is a failure to be like Christ. He intervened at a great cost to himself to hold us back from the slaughter of sin and the second death—even though he would have been just in letting us perish. How much more then, should we be willing to heed his call to prevent the innocent from perishing and obey his command to see justice rain down upon the earth? In our sins, we were just as helpless as unborn children before the forceps and knife of the abortionist, and God intervened and rescued us. Dare we tell him in return that we cannot be bothered to help rescue the unborn? Like the civil war Israel fought to avenge the wickedness of Gibeah, pursuing justice for the unborn and intervening for their deliverance may prove costly, but whatever its price, it will never come close to the price Christ paid for our deliverance and the satisfying of the Father’s perfect justice.

For the Christian, repentance is not just the exchange of one set of actions for another, repentance is ultimately the realignment of the self to its death and the imitation of Christ. All our pursuits of justice must start and end here; our throwing off of inaction and a robust commitment to deliverance and justice-seeking must take shape within our commitment to be like Christ. With renewed adoration for who he is and what he has done, let us ask the Lord to conform us to his image and ready us to be vessels of deliverance and justice for the unborn in whatever way he so desires. If we pray with sincerity, there is no doubt he will give us what we ask.

Notes

1 For this observation, along with so many others in this essay and the last, I am heavily indebted to John Ensor and his book Innocent Blood, which succinctly, powerfully—and, most important—biblically, details bloodshed and the Christian response to it. His thoughts have proved to be a large tributary to the river of my own in developing a biblical perspective on abortion.

2 As referenced in part one of this series, Scott Klussendorf gives a succinct syllogism concerning the grave immorality of abortion: “Premise 1: It is wrong to intentionally kill innocent human beings. Premise 2: Abortion intentionally kills innocent human beings. Conclusion: Therefore, abortion is morally wrong.”

3 This is not to say that issues arising from abortion or the issues that feed it are without complexity. How to help an unemployed, single mother of two, with nothing more than a high school education, who has been abandoned by her boyfriend and the father of her third and currently gestating child is never a straightforward or quick endeavor; she is the victim of a confluence of social ills, each one on its own dauntingly difficult to address at a systemic level. Solving the question of abortion’s morality is an easy one; solving all the societal difficulties and pressures that may tempt one into having an abortion is a different matter. But the difficulty of entrenched structural maladies has no bearing on the wickedness of the act of abortion itself and the corresponding moral imperative to intervene and stop it.

Our society is currently plagued by a morass of sexual addictions and dysfunctions that have no doubt lent themselves to the sickening high statistics of harassment, rape and abuse in this country; but no one dares suggest—unless they want to subject themselves to near-universal outrage and scorn—that the prevalence of these addictions and dysfunctions in any shape or form excuses or blunts the incalculable evil of rape and sexual abuse. Cultural and societal environments can make it easier or harder for different evils to grow, but one cannot use the climate to misclassify the fruit it helps bear. Instead, we should use the ease or difficulty in which immorality grows to diagnose the moral health of the culture itself. Utilizing this approach, it is beyond plain that our nation and society is desperately sick.

*Unless noted, all scripture quotations taken from the NASB. Copyright by The Lockman Foundation.