Note: this is part four in a series of essays examining the issue of abortion biblically. Click here for part one, here for part two, and here for part three.

Hero Making

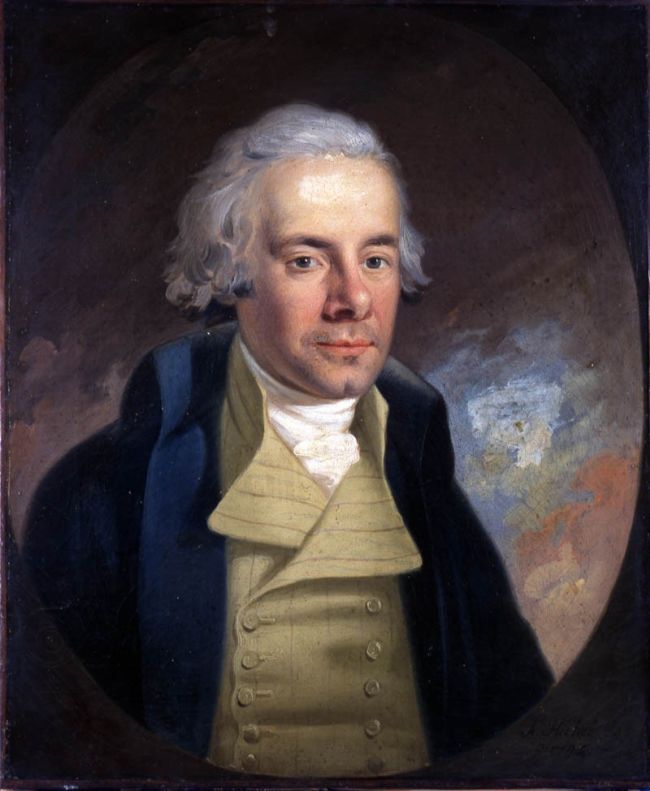

True Christianity lends itself to heroics. Rightly understood and lived out, no other system of belief is more apt to foment acts of bravery and rescuing among mankind. From Corrie Ten Boom’s hiding of the Jews and Dietrich Bonheoffer’s clandestine church and resistance efforts under Nazi rule to Brother Andrew’s Bible smuggling and Jim Eliot’s outreach to violent indigenous tribes; to the tireless and protracted efforts of John Newton and William Wilberforce to the end British slave trade or the extraordinary lives of St. Francis and St. Patrick, the Christian faith has no shortage of personages, ancient or modern, worthy of the title hero.

Indeed, the origins of the word “hero” itself find their closest fulfillment in the annals of God’s written word. Taken from a root word in Greek that meant “defender; protector,” the word hero originally meant one who was a demi-god: part man, part divine; a person endowed with supernatural strength or ability used in the service of righteousness to protect and rescue others. Throughout disparate centuries and cultures, stories of men and women engaged in deeds of outsized bravery and righteousness have captured the minds of children and elders alike; tales of individuals who by their great strength and marvelous powers aid the oppressed and vanquish agents of darkness whether they be kings, raiders or monsters. Men and women of outsized stock who stand apart from the rest of humanity; otherworldly, they seem, and often quite literally are, divine.1

No demi-god, Christ was God himself come down in human flesh to grant humanity a mighty deliverance from the unbreakable shackles of sin. He exceeds the heroic ideal—what humanity had dimly hoped for was not enough. No hybrid being would suffice for deliverance from doom; mankind needed one among them fully man and yet fully God. Brimming with love in his heart and undaunted in the face of death and the spiritual agony of the cross, Christ undertook the greatest display of love and bravery the cosmos will ever behold and accomplished the greatest feat of rescuing time will ever see, triumphing over the powers of darkness once and forever. He is the King of kings and the Lord of lords, and to that, we might add, he is the Hero of heroes. All true acts of heroism are but shadows cast by the light of his own. Because humanity has been made in the image of God, at our best moments, pale reflections of what he is the substance of shine through.

If the Christian is called to pursue acts of justice—acts of deliverance and advocacy for the oppressed, as we have contended he or she is—then he or she is called to display this heroic nature of Christ. Fighting against injustice and oppression is not a task fit for the weak or cowardly, it requires bravery and strength. One must have both the power necessary to be effective over forces of injustice, and the courage to use such power in the face of suffering and daunting opposition. One quality is not much good without the other; a hero has both. Thus, the call to pursue justice, and more particularly to our purposes, the call to rescue the unborn, is a call to heroics. If God has commanded us to “deliver those who are being taken away to death” (Proverbs 24:11), then he has commanded us to engage in heroism. How to be such a people we shall undertake to explain.

As we chronicled at the conclusion of the last essay, the failure to pursue justice is ultimately a failure to pursue Christ-likeness. Implicit in that statement is the assumption we have the ability to pursue Christ-likeness, as failure implies something other than mere inability. The young boy grieves himself over his sixth consecutive strikeout in the little league games in a manner he does not when he spreads his arms and leaps from the roof of his house in an attempt to fly. The former deals with possibilities, the latter does not. Truth be told, the pursuit of Christ-likeness is more in line with the boy’s rooftop aspirations than it is with his home-plate endeavors. It requires of us something we don’t have in and of ourselves—something contrary to who we are. The boy needs a set of wings; we need a new nature. Just as he cannot set sail to the skies without those feathered appendages, so are we unable to ascend to heaven’s lofty heights without a deliverance from sin and transformation of soul. And only God can supply it.

The story of the gospel is that there is only one hero. There is only one able to rescue and render justice for the world’s evils. And none of us qualify. Sin had made the whole of mankind both prisoners and villains—or, perhaps better said—prisoners to being the villain.2 The gospel starts with the terrifying truth that God comes to enact justice, not on our behalf, but on his behalf against his adversaries, who are those who have broken his laws and besmirched his glory. And man, in his natural state, is God’s foe. What a wretched state to dwell in! Sin was what enslaved us and what we needed rescuing from, and yet sin was what made us enemies to the only one with the power to rescue us. We were like convicts with a terminal disease whose judge was also our doctor, the only cure for our sickness residing in the hands of our executioner.

A true hero is both compassionate and just. But when Satan tempted Eve and Adam fell, he tried to strip the world the chance of ever beholding one. He put God in the ultimate conundrum: spare humanity and be unjust, or destroy humanity and render sin more consequential than mercy, which is an aspect of love. But the Almighty cannot be beaten. Taking the punishment for our sins, Christ satisfied the justice of God; his death freed us from sin’s enslavement and healed us to live lives of righteousness (1 Peter 2:24). Our executioner sat in our electric chair and gave us our medicine—justice and mercy accomplished in one act.

This is the good news, and it holds implications for us. All salvation and justice come from God alone. In need of rescue, we were unable to save ourselves or others; as villains, we lacked the ability to bring justice to the world’s myriad evils, standing condemned as those who must receive Justice’s inescapable and fatal blow ourselves. As pertains justice, God looked down on the earth and saw that there was no man able to bring it, so he put on his war garments and went to dispense it himself (Isaiah 59:15-18, Isaiah 63:3-6). He says of his quest for justice, “from the peoples there was no man with Me” (Isa 63:3). Salvation, deliverance, and judgment were undertaken by him and him alone. Why do we start here? Because the first step to true heroism is recognizing that there is and will always be only one who is truly heroic: Christ. Only Christ had the love, courage and power necessary to save; the rest of us needed saving. Left to ourselves, we only had the power, perhaps, to choose which particular flavor of villainy we wanted to aspire to. To be anything other than the prisoner and villain is a miracle wrought by the heroic work of Christ.

Gospel Responders

What that necessarily implies is that any and all works of heroism we undertake are derivative of his own; all acts of saving have as their origin and their possibility the salvation that comes from Jesus Christ. Why do we as God’s people rescue others? Why do we intervene on behalf of the unborn? Why are we able to? Because God has already rescued us. His rescue is the source of ability and motivation behind our own. Hence, all true justice is done in response to the gospel.

By this, we mean that for Christians, pursuing justice is an expression of gospel gratefulness. We have dealt at length with the grievous consequences that await those who fail to pursue justice, and how our inaction to the shedding of blood makes us complicit in it and positions us to be recipients of a terrifying divine judgment. Such truths produce a holy fear in us that banishes our inactivity and complacency—and they are meant to; it is the fear of the LORD that starts and keeps us on the path of wise living (Proverbs 9:10). But as Christians we must take pains to understand that God does not desire us to act only because we are afraid of his judgments; he wants us to part ways with our inaction because we love him and have a heartfelt desire to be like him. In gratefulness for what He did on the cross, we are to freely give him our glad service; and in adoration for who he is, we are to make him the object of our earnest emulation. Thus our fight against injustices and our effort to rescue others is one of thankful imitation. After all, is it not so that the heroes that receive our highest venerations are the ones we aspire to imitate?

By saying all true justice is a response to the gospel, we are also speaking of causality: true justice is the result of the gospel and an expression of the gospel—and hence an expansion of the gospel’s work. In other words, acts of true justice embody and carry within themselves the message of the gospel and are themselves manifestations of God’s saving power. Every form of deliverance and every act of compassion has the gospel as its genesis and is designed to be an expression of the gospel because whatever we do, we are only doing it because of what Christ did. Without the work of Christ on the cross, there would be no work for his disciples to attend to. And, if the gospel is the real reason for our work, then in our work we will not fail to let people know the reason. Deeds always beg the question of motives, and even when not explicitly asked, those who are highly motivated by the love of something or someone cannot help but confess to others the raison d’être of their actions—to do otherwise would seem to be a betrayal to the object of their love. So it is that if the love of Christ on the cross compels us to works of justice, we will want the recipients of those works both to know his love and to know that it is love for him that motivated us to perform them. Every outstretched hand lifted up from a miry clay, every hurt man or woman held and bandaged by the saints, in asking, “Why did you do this?” should hear from a follower of Christ’s mouth: “Because this is what Jesus did for me; I am here to help you only because he has sent me.”3

The importance of this cannot be overstated. As his people, God sends us out not to bring people into our rescuing, but into his. The heralding of the gospel is telling others what Christ has done for us so that he might do it for them. We do not bring people to salvation—Christ does, but he uses us as a means to bring the lost to himself. And so with every other form of rescue. To God belong deliverances from death (Psalm 68:20). The poor and needy are fed and rescued by his hands (Psalm 146:7, 68:10, 109:31). While instances of supernatural intervention are often portrayed only as unmediated encounters between God and the person helped (or else with some assistance from angelic beings), the truth is that the help a saint offers is no less supernatural. As many have pointed out, if the Church is the body of Christ, then we are his hands and his feet, which means that behind our footsteps and outstretched arms are his own. If Bob’s hands build the cabin, then the builder of the cabin is Bob. It follows then that if Christ’s hands feed the poor, then the one who has fed the poor is Christ. Thus, in all the work of the Church, Christ is working.

If our rescuing is both made possible by and done in response to his rescue of us, and if our works of justice are acts of obedience conducted as servants in response to the commands of a king, then it is not accurate to claim we have rescued or rendered justice for anyone—Christ has, through us. Each action of deliverance and justice is just the latest in a series of dominoes to fall which began their cascade at the cross—they are part of the onward sweep of his love and saving power across space and time, Calvary the site of detonation blast that forever extends outward by the activity of the saints.

None of this is meant to distance us from the urgency of taking action or blunt our responsibility to work justice and rescues—it is meant to frame it. In reflecting on his work among the apostles, Paul did not shy away from declaring what he had done: “I labored even more than all of them.” But to such a declaration was joined the addendum, “yet not I, but the grace of God with me” (1 Corinthians 15:9-10). Prior and more fundamental to the “I” of his labor was a “not I,” one for whom the credit of labor was more rightfully due. Our labor against injustice must be vigorous, but reverentially and humbly recognized as empowered by the vigor of another.

Many a Christian has had as part of their journey the realization that while they claim to be saved by grace alone, by their deeds and attitudes it is evident they have been under the gospel of works, seeking to gain the favor and acceptance of God their creedal statements already claim they have been bestowed with. In a similar manner, increasingly unnoticed perhaps in our time, Christians can proclaim Christ is the solution for others while acting and living as if they are the answer to mankind’s ills.

Nowhere is this more evident in our present hour than in the multitude of calls to action on behalf of that ever so amorphous term, “social justice.” Such a topic cannot be delved into at any great length right now for our present purposes, but suffice it to say, the myriad of causes under the umbrella of social justice, legitimate and illegitimate, too often have as their key ingredient and tenet a belief in the power of human will and effort to bring forth justice and redemption. In many Christian circles where social justice has become the locus of church engagement, the name of Christ may be invoked and his example held up as a model of inspiration, but as a source of power, he is squarely in the background; what man can do takes the stage—front and center. But when man’s ability is the focus, man is what will be trusted in, and man is what will be worshipped. Whenever this happens a true pursuit of justice has ceased.

This distinction is no small one. It is not a case of splitting hairs—it is everything. For in it lies the divide between an authentic pursuit of justice and a false one. The call to justice is a call to action. We must get up and get involved. But knowing why we act, and knowing why we are able to act is critical and foundational. Misstep here and the heeding of the call will have been in vain. The work of justice is not done to earn us favor with God (his favor is something we already have and can never earn) and it is not done to make us look or feel valuable or important—it is not a vehicle for self-glory. It is not about what we can do or accomplish by our efforts; it is about what Christ has accomplished, and what he can do through redeemed vessels purchased by his blood.

Hence, in our confrontation with the horrors of abortion, saving the unborn must never become a vehicle for self-righteousness, it should always be done as a response and an expression of the gospel from those who have joyfully received its tidings. For every child saved from the pill, the vacuum, the forceps, and the knife and for every mother lovingly counseled out of fear and selfishness from a decision one day she will sooner or later regret; when they ask their rescuers “Why?” they should receive one answer: “Because Christ did the same for me.” We rescue the unborn because Christ rescued us. And in our rescues, we bring them into his rescuing.

Superpowers

In Luke 4, Jesus enters Nazareth’s synagogue, unrolls the scroll of Isaiah, and reads:

18 “The Spirit of the Lord is upon Me,

Because He anointed Me to preach the gospel to the poor.

He has sent Me to proclaim release to the captives,

And recovery of sight to the blind,

To set free those who are oppressed,

19 To proclaim the favorable year of the Lord.

(Luke 4:18-19)*

After closing the scroll, Jesus declares, “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:21). The Spirit of the Lord was upon Jesus for a purpose. He was the Christ, the “anointed one,” and the ministry Jesus was anointed for was one of rescue and deliverance. Jesus was the hero Israel had been waiting for. And “waiting for” must be emphasized. They had Moses to lead them out of Egypt, Gideon to rescue them from the Midianites, Sampson and David to deliver them from the Philistines, Esther and Mordecai to save them from the decree of Haman the Amalekite—but none were the promised Messiah who would liberate and rule his people with peace and justice. From Israel’s time in the promise land to their exile and return under Persian, then Greek, then Roman rule, their history was one of much oppression; with seasons of reprieve that fostered temporary or partial deliverance by the hands of the men and women God had raised up. But the one who would bring total and lasting freedom had yet to come, and his arrival was anxiously longed for generation after generation, century after century, until the day Christ set foot in that Nazarene synagogue. It had taken centuries for the Hero to come.

Embedded in the idea of heroism is rarity. If society has heroes dime-a-dozen then there is no need to venerate them, nor are they to be sought and wished for with any great intensity. Since they are always around when you need them, your need for them will not be very great, and the myriad forms of hydra-headed wickedness will have been hacked to julienne-sized pieces of darkness by the efficient overkill of a thousand swords. The narrative appeal of a place like Batman’s Gotham of course is that there is one Batman and a thousand villains to contend with; a thousand Batmans with ten villains in town would not be any child’s favorite comic. This is because such a lopsided power dynamic does not conform to our intuitions of reality. The earth is a dark place; sufferings wrought by a plethora of evils abound. The Scriptures themselves declare that “darkness will cover the earth and deep darkness the people” (Isaiah 60:2), and that “the whole world lies in the power of the evil one” (1 John 5:19). For humanity, darkness pervades; and in its shroud, we search for glimpses of light. When a hero appears, it is an event of utmost significance.

It should stun us all the more then, that as his people, Christ has ordained that we be like Him. At ancient Antioch, the followers of the Way were first called “Christians,” that is, “little Christs.” Having entered the world and ascended back to Heaven, Christ did not intend for his presence on earth to be a quantitatively singular event; the whole world was to be filled with people who displayed His glory. Until his second coming that event will remain qualitatively singular, yet despite this, we are still told by Christ that his people, his “little Christs,” are called to do the same works he did while on the earth and even greater ones.

How can this be? The same Spirit that dwelt inside of Christ and descended upon him when he rose out of the Jordan is the same Spirit he promised to pour on his disciples for divine empowerment and the same Spirit now taking up residence in each of his children’s hearts. This Spirit is now within and upon his followers, who are “little anointed ones.” And guess what? The divinely-empowered task has not changed. We are still called to preach the gospel to the poor and proclaim that release to the captives has come through the shed blood of the Messiah. And, we are still called to, “set free those who are oppressed.” The Spirit conforms us to Christ’s image, both in character and deed. We are to think and feel as Jesus thought and felt, and we have been given what Jesus was given so that we can do what Jesus would do. The rarest of all beings, now that he has come, is supposed to seem to the world a little less rare in encountering.

This is a wonder of the gospel. We were once villains; the Hero has rescued us—and the nature of his rescuing was to take our villainous souls and transform them into heroic ones. Christ the hero came and stood alone. But now that he has come, he is no longer alone. His victory over darkness has now unleashed Christ-in-miniatures all over the earth, reborn with a new nature capable of true heroism—the boy on the roof can now fly. Christ now stands as the Hero all true heroes look up to, and unlike the demigods of Greek mythology, these heroes are mere humans—but God lives inside them. In this regard, the necessity implied within those myths—that we are in need of divine humans to rescue us—was not far from the truth. Divinity and humanity comingled once walked the earth, and walks it still; inside the hearts of the humble, unassuming men and women all across the earth whom he has come to dwell in. They are now the earth’s heroes—simply, and only—because the Hero lives in them.

That, dear Christ-follower, includes you. While the dangers of self-glorification that could arise from a perverted embrace of this truth are real and evident, there remains the greater danger of dishonoring God and robbing him of his glory from neglecting it. We must not devalue the Spirit of God by devaluing the implications of the Spirit of God being inside and upon us. Through Christ, we have been called to perform valiant, mighty, and effective deeds. To live a life other than this is to live in opposition to who he has created us to be. The world lies under the power of the evil one; a dark pall of hopelessness and cruelty surrounds the lives of untold many; and in every country, town, and city lurk those whose souls have been twisted into an ever-darkening resemblance to the image of Satan—a lion, prowling around in search of those whom they may devour. Into this miasma he has sent you, just as the Father has sent him (John 20:21), to be to the world as a star, burning clear and refulgent against the blackness of night (Philippians 2:15).

We do him no honor by shrinking from the sending. We are what we are only by his hands, there is no room for boasting, and indeed to be what God intends for us to be can only come through a deep and abiding humility that well understands the words of the Lord: “Apart from me you can do nothing.” It is was in the moment that Peter, overwhelmed by the holiness of the one who called him said, “Go away from me Lord, for I am a sinful man!” But to this, he was told: “Do not fear, from now on you will be catching men” (Luke 5:8-11). So it is that when we recognize what we are apart from Christ, we can begin to become what we are when we are with Christ.

In Job 29, the eponymous sufferer declares:

11 “For when the ear heard, it called me blessed,

And when the eye saw, it gave witness of me,

12 Because I delivered the poor who cried for help,

And the orphan who had no helper.

13 “The blessing of the one ready to perish came upon me,

And I made the widow’s heart sing for joy.

14 “I put on righteousness, and it clothed me;

My justice was like a robe and a turban.

15 “I was eyes to the blind

And feet to the lame.

16 “I was a father to the needy,

And I investigated the case which I did not know.

17 “I broke the jaws of the wicked

And snatched the prey from his teeth.

(Job 29:11-17)

Because of Christ’s Spirit, what Job said of himself can now be what we say of ourselves—if we choose to live it. Justice can be our clothing—not just for special occasions, but our daily wear. When the Spirit of God is upon us we can break the jaws of the wicked; we can shatter the sharp teeth of the abortion industry and its pervasive culture of death that in greed and without mercy devours the unborn and tears at the souls of women and men. We can rescue victims out of their clenching grasp. The unborn that stood ready to perish can grow up and become the tongues that bless God and bless us.

Ex Fide Fortis

Abortion is a deeply entrenched evil within society, maintained and guarded by the forces of hell. But the spirit of Christ is mightier, and “greater is He that is in you than he that is in the world” (1 John 4:4). This is no rah-rah-summons or pep rally. Confronting great evil requires great courage, and the truth is, only Christians are justified in possessing it. While God requires utmost humility in ourselves, that humility is meant to be expressed in utmost confidence in him. If he is to have within us the heroic hearts he is worthy of, he must have a people who believe that his mighty power to save comes not only to us but is able to come to others through us.

In his zeal to rescue the unborn and stop the shedding of their blood, God is looking for men and women who feel woefully unequipped in themselves to do anything about it. He is not looking for self-assured crusaders to jump with him into the fray. Truth be told, if we are not overwhelmed by the colossal magnitude of this systemic evil to the point of near-despair, we are not seeing as we ought. It should be despairing enough to stand in front of one abortion clinic and watch dozens of men and women walk in to destroy their child, let alone to contemplate that such a scene is happening simultaneously with the one being witnessed in thousands of other cities across the country, and to know these daily horrors are celebrated and given ideological justification in our newspapers, television shows, schools, and even our pulpits. Such realities, rightly contemplated, bring men to their knees.

Yet in that place despair does not have to remain. Systemic evils force us to look beyond ourselves—beyond our capabilities and strength, to have a clear vision of the one who says, “Is anything too difficult for Me?” (Jeremiah 32:27). We lift our eyes to the mountains and ask where help can come from, and in so doing we receive an understanding that the one we serve is the one who causes the mountains to melt like wax and the one who puts words in our mouths that can uproot mountains and send them plummeting into the sea.

After all, the world’s true heroes (those whom the world was not worthy of) have always been defined by their great trust and unshakable faith in the Lord. It is was by faith that they conquered kingdoms, shut the mouths of lions, quenched the power of fire and from weakness became strong (Hebrews 11:33-34). As the warrior-king and hero David exclaimed, “For by You I can run upon a troop; and by my God I can leap over a wall” (Psalm 18:29). David’s confidence in performing these heroic feats stem from three words: “by my God.” In seeking to rescue the unborn, God is looking for individuals who will say those three words, then live by them. When commanded by God to rescue the unborn, obedient disciples who know they do not have what it takes will earnestly ask for the Spirit to be given to them, and this God will supply—in lavish measure. They will go forth to their work in great faith and great power, and their work will not be in vain.

The truth is, like heroes, such people remain rare—far rarer than God has intended. He did not crush his only beloved son and promise the gift of Spirit to make for himself a people who act and live as if they were feebly endued by it. There was never meant to be an aristocratic divide in the Christian faith—a small group of individuals who truly know and live by his power and a swelling mass of commoners who do not. There is a multitude of assignments and callings in the kingdom, but the power of the Holy Spirit is to mark and enable them all. As there are many parts in the body and yet all parts depend on oxygen to survive, so is it that none of Christ’s body and its various parts have been designed to function without the Spirit’s power. Yet far too many of us live as if our air were cut off.

The world needs Christians who live otherwise. The unborn need men and women who believe God is mighty to save—and will not quit knocking on heaven’s door until they became conduits of his mighty salvation. Above all, God is, not in need of, but wholly worthy and deserving of, individuals who seek to be used by him in matters of justice, not first and foremost for the sake of the world’s inhabitants, but the sake of his glory; knowing that ultimately justice is a matter of God getting the glory due his name, and that rarity of heroism in his people should be sought as a thing to make less rare, precisely because in being made less rare, God will be glorified all the more, and men will give thanks and praise to the only one worthy of it (Matthew 5:16). If our hearts burn to be such men and women, we need do nothing more than bow our knees and stare at the cross. If we gaze upon Christ and him crucified long enough to catch a true glimpse, our hearts will break, and nothing will dissuade us from praying for holy power and staying on our knees till it arrives. When it does, we shall rise up and take our stand for the oppressed and unborn.

Notes

1 Take for example Homer’s Achilles or the Greek legends of Hercules. Both were the products of humans coupling with the divine; the former by a human king and water goddess, the latter by Zeus and a woman. Such beings were entirely fictional; whatever personages that may have inspired them, figures like Achilles and Hercules never walked the earth. Yet the longings of the human heart captured by the imaginative tales about them are quite real, revealing over millennia the collective longing of the human race for a savior, one who is divine and yet present among us in our sufferings. In short, they reveal a veiled longing for Christ.

2 Romans 5:6-11 elaborates this state quite well along with succinctly explaining the saving work of Jesus Christ. In verse 6 it says: “For while we were still helpless, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly.” Christ did not die to lend us a helping hand or give us a holiness boost as it were, like a child who needs a bit of help to climb over a fence. Our state was one of complete helplessness, imprisoned without any hope of freeing ourselves from bondage to sin. Romans 6:17-18 says that before Christ we were slaves to sin, that is, we were not voluntary servants who granted or withdrew our obedience to sin based on our own whims so much as we were forced to obey sin’s injunctions like a slave would. For a volunteer, his or her will is preeminent and instrumental in their actions, for the slave his or her will is of no consequence. What they would like to do has no bearing on what they must do and will do because they are slaves to someone else. The good news is that Christ has freed us from sin and made us slaves to righteousness (verse 18). Verse 10 of Romans 5 says: “For if while we were enemies we were reconciled to God through the death of His Son, much more, having been reconciled, we shall be saved by His life.” Our imprisonment to sin meant that Christ died for us not while we were his friends, but while we were still his foes. Before he saved us, we were indeed prisoners to being the villain.

3 Because he has sent me. Christians are “sent ones.” That means we did not send ourselves. And because we did not send ourselves, we do not get the credit for whatever work we do while we are sent; the one who sent us does. When a convict on death row is granted a last-minute stay from the execution chamber by the governor, the convict does not make the warden who comes to tell him the news and to halt the execution process the object of his gratitude. He gives thanks to the governor whose authority the warden was under and bound to. So it is with us. We are under the authority of another. And like the warden, we are not the source of a man’s salvation, just an instrument in which it is carried out.

*Unless noted, all scripture quotations taken from the NASB. Copyright by The Lockman Foundation.

** The title image is taken from a 14th century manuscript of The Golden Legend, a series of hagiographies. The picture depicts the legendary St. George, of whom little is factually known, in his most legendary of acts: slaying the dragon and freeing the princess to whom the dragon was given as a human sacrifice.